Alamieyeseigha – His Day Is Done

November 11, 2015

TRIBUTE TO CHIEF DIEPREYE SOLOMON Peter ALAMIEYESEIGHA (“DSP”)

February 25, 2016I KNOW MY MOTHER HAS GONE TO HEAVEN

Mother is the name for God in the lips and hearts of children – William Makepeace Thackeray

I was with my mother in her farm at Ovom bush that November afternoon, when two men came to talk to her, and then she screamed, fell and cried. I do not remember how we got home. I was crying because my mother was distraught, crying and wailing. But, later that evening I cried for the reason that would come to define my life. I was ten (10) years old when the news came that day that my father, one of the best brains in Attissa, son of Yenebebeli, one of the first people to build a modern (block) building in Yenagoa, a headmaster of outstanding pedigree, was dead. I cried. For me, I thought to myself that my life had come to an end.

I was with my mother in her farm at Ovom bush that November afternoon, when two men came to talk to her, and then she screamed, fell and cried. I do not remember how we got home. I was crying because my mother was distraught, crying and wailing. But, later that evening I cried for the reason that would come to define my life. I was ten (10) years old when the news came that day that my father, one of the best brains in Attissa, son of Yenebebeli, one of the first people to build a modern (block) building in Yenagoa, a headmaster of outstanding pedigree, was dead. I cried. For me, I thought to myself that my life had come to an end.

The next day, my mother, Abirindi, daughter of Chief Fefegha, who challenged the Colonial Royal Niger Company, picked herself up, dusted herself from the floor where she sat, took me by the hand, walked me to Yenagoa waterside, bathed me properly and said to me, “Son, your father wanted you to go to grammar school, that was his wish. I will sell my last wrapper to make sure you go to grammar school. Weep no more.”

Maxim Gorky, that Great Russian writer was right when he said, “Only mothers can think of the future – because they give birth to it in their children”. The love of a mother can propel a child to greatness. I was raised by a single mother who worked twenty-five hours a day, to make things easy for me. She would leave home for her farm before the cock crows at dawn, and return at dusk, rarely before 7pm, and still go to the village square to buy ingredients for soup, having brought yam and plantain from her farm. On her way home from her farm, she would stop to check on her fishing trap, but she must come home to make that late dinner. Then, according to her, by her culture she must clean up the dishes. Then, she will begin to prepare and select the Adia (yam seedling or the Okile (cocoyam) for planting, and then again she would begin to weave the Ikeli (traps for shrimps) or the Ukpom (Basket) that she must sell on Edeafieki (market) Day. Thinking back now, those memories remain hazy, yet vivid at the same time, and I am at a fog in remembering those events or happenings. Were they real? Did my mother normally stay awake all night? Oh yes, I remember when she was weaving the Ikeli or Dumu Utaran (Pounding the Fufu). She told me and friends, especially my Cousin, Domokumo, tales of her great grandfather and father; how her grandfather gave the land to the Anglican Church and St. Peters school, Yenagoa. She also told me then that my paternal grandfather, Iwemu, was a wrestling champion and how my grandfather brought the Anglican Church to Yenebebeli, and how my father, Christian Stephen, was the most handsome Headmaster in the country. I never was interested in this part of her stories. The part that captivated my attention was Ifiama, a wizard, a woman that was operating an invisible television in Yenagoa. She could tell tomorrow. She predicted outcome of wrestling competitions. She was simultaneously feared and revered throughout the land. She also told me stories of her forefathers’ immigration from the Bini Kingdom. In fact, she told me about Oguara, a great Bini giant of a man, who could uproot a palm tree to sweep his compound. A man who could pull down Aka (Iroko Tree) with one hand. She told of the great deceit of Iwiri (Tortoise) and how he manipulated the birds to let him fly with them and explained why tortoise has cracked shells.

Looking back now, I continue to marvel at the intelligence, wisdom and the information that was stored in that smallish head. Engr. Izi Faafa, who has interacted with my mother on many occasion, particularly during our time in Lagos, concluded that Abirindi was one of the most intelligent women he had ever met.

Truly, my mother did not attend a formal school, but in my mind, she was one of the most educated persons I have ever met. If I am to score my mother I will give her an ‘A’ in Literature, an ‘A’ in History, an ‘A’ in Languages (my mother could speak many languages – pidgin English, Nembe, Kolokuma, Epie, Kalabari, Okirika, passable Yoruba, passable Hausa, passable Bini), and an ‘A’ in Agriculture. It was years later when speaking with Professor Zehlia Babaciwilhite, a Professor of linguistics at Berkeley that I began to appreciate the depth of knowledge stored in my mother’s head. In fact, my mother was the unrecognized professor of languages. Long before I went to study Agriculture to Ph.D. level, my mother had taught me crop rotation, land fallow system, shifting cultivation, irrigation, seed multiplication, bio fertilizer, compose manure, multiple cropping, erosion control, crop preservation and a host of other concepts related to sound farming practices.

I arrived in the Soviet Union on a Federal Government scholarship to study medicine, but the authorities decided that in the city where I was posted, the quota for medical students had been exhausted, and consequently, I was redirected to the field of agriculture. I spent days on my return to Nigeria during the holidays, explaining to my mother that I was actually studying agriculture, not medicine, and when she finally understood what I was saying, she smiled and said “You see, that’s why it is good to follow your mother to the farm; I have already taught you all of that.” Indeed, she had taught me all that. Mother had several farms. One was in Uto Kpakaram at Ikolo, and others in places like Azibani, Ukobode Yenebebeli, Otoro Famgbe, Azi Swali, Okotumo Ovom, Eti Fitepigi and Igbene Ozubidebide. We would go from one farm to the other, planting and harvesting the crop of the season.

Yesterday my paternal cousin, Effort Dokubo, sent me a text commiserating with me on my mother’s death and brought sweet memories to my mind’s eye. He reminded me that, he, along with his mother and others in a canoe, as well as me with my mother in a canoe, all rowing by hand, were travelling from Yenagoa to Warri and my mother, ever caring, would call out Etiemo (my sister), that we should stop at the next fishing port to eat something before moving ahead. It was a tedious, painstaking job, manually rowing a canoe on a journey which took about five days, a journey in which we would sell our wares in villages along the way. I travelled on many occasions with my mother to far flung places such as Ukubie, Ozezama, Basambiri, Ogbolomabiri, Okpoama, Twon Brass, etc. My mother would buy plantain, yams, cassava at Oyoyo Market at Ovom and would sell these items by barter (in exchange for dry fish), from village to village during the flooding season when there was no farming, and bring this fish back to Yenagoa to sell them at the Oyoyo Market. Years later as Secretary to the Government, I was instrumental to moving the Oyoyo Market to Swali when Governor Alamieyeseigha completed the building of the Swali Market .

My mother taught me about the power of inspiration, hope, love, compassion, generosity, sincerity and loyalty. She did it with the strength and passion that I wish could be found in every mother. By the time I was in my teens, I had unknowingly become a gentleman, respecting and treating women with absolute respect and tenderness.

My mother and my late sister, Cecilia Zifawei, taught me how to respect the virtues and values of a woman. Both overworked themselves trying to play the dual roles of man and woman, father and mother, in the home. Unfortunately, Cecelia died five (5) years ago, and I am yet to recover from her untimely demise. I blame her for making me an only surviving child. I blame her for dying; leaving me alone to bury my mother, a task that she could have done much better than me. I blame her for leaving me alone. I blame her and I refuse to forgive her. Her death has given me too much pain and now this blast – “Alamieyeseigha”.

You can shed tears that Abirindi is gone or you can smile because she has lived the fullness of life. Abirindi lived for over ninety (90) years. Her only surviving brother and my uncle, Chief Costman Fefegha, told me that by his calculation and judging by his own age, my mother was at least ninety (90) years old, maybe even more.

Abirindi had two surviving sisters –Baby and Erebigha, and a brother, the aforementioned Chief Costman Fefegha. Their parents, my grandparents, died when my mother, Abirindi, was about fourteen years old. To take care of her younger ones (Baby, Erebigha and Costman), she decided to marry at an early age in order to provide for her siblings. By all accounts, she did a great job, as each of them became successful in their own right. Both of her sisters had many children and my mother’s only surviving brother has more than seven children and many grandchildren.

So, who motivated me to be the man I am? The answer is simple – my mother. My mother may have been considered “illiterate” by academic parlance, but she was by far, the wisest and most learned person I have ever met. She was a peasant woman, petty trader, basket weaver, fisher woman. She struggled all her life and did menial jobs, such carrying loads, cleaning. She taught me about the dignity in labour, a lesson which proved invaluable during my years in the Soviet Union.

Throughout my life, my mom has been the person that I have always looked up to; her smile an inspiration, her suffering a source of courage and her lack of a formal education, a vivid reminder for me to remain humble.

I remember my mother’s prayers and they have always followed me. I believe even now as I write, mother is still praying for me and my family.

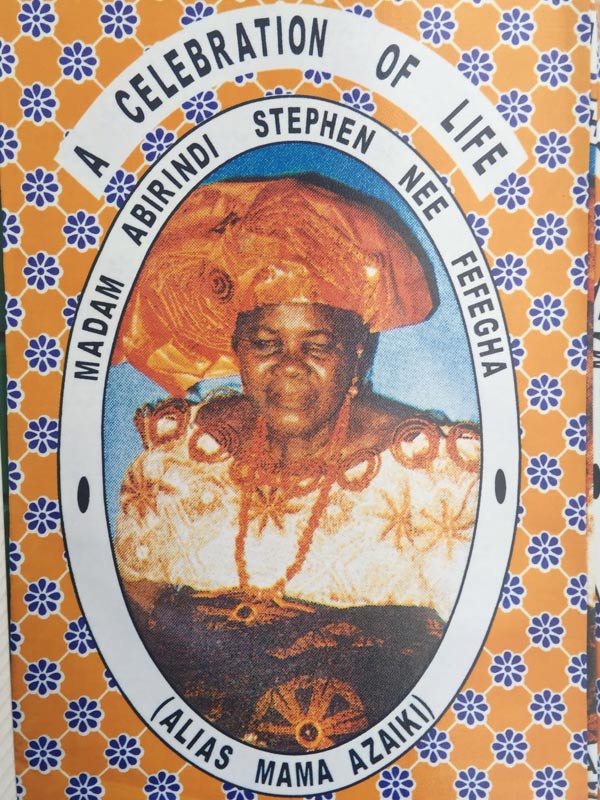

The legacy of my mother, to me, is her generosity, kindness and love, all of which were infectious. Her humility, Godliness, and smiles were the true manifestation of Godliness – love. Growing up, my mother’s house was a dormitory, kitchen, restaurant, store, bank, market, school, everything. My mother, unlike most women I knew who would send you away when it is time to eat or will tell you your friend is not at home because it is time for them to eat, was quite different in this regard. My mother would actually send me three (3) kilometers to go call my friend or cousin or whoever, to come and eat with me during meal time. She taught me values which I never believed possible to practice. She was Mama Azaiki, Mama Yenagoa, Ina Gene, Ina Eni and later people began calling her Mama Africa. How this Mama Africa came about I do not know.

Growing up, I saw my mother as the most beautiful woman – dark, petite, white teeth, swaging steps, curvy lips and a fixed smile. My mother never forgot, not even for a moment, that she was the daughter of Chief Fefegha and a princess. It was that dignified humility that distinguished her in a crowd – stoic and proud, yet calm and humble with impeccable comportment. I owe everything I am today, to my mother, and even then, I cannot compare to her greatness. I attribute all my success in life to the moral, intellectual and physical education I received from her.

In 1992, I returned home finally from the former Soviet Union with a Ph.D. in Agriculture. The Epie and Atissa Communities decided to do a befitting welcome party for me. Thanks to Patterson Kikile, Amasamana Ikiobofa, Sinivie Ototo, Noble Akenge and others. At that reception Chief Frank Omeleh of Yenaka was the Chairman. In attendance was the Obeni Ibe Epie (Clan Head), Chief Charles Agulata and Ebeni Ibe Atissa (Clan Head), Chief B.L.W. Mabinton. It was at that occasion that the greatest gathering of the two clans to celebrate an illustrious son took place. It was at that gathering that I saw an emaciated, worn-out, malaria/typhoid ridden, almost dead woman – Abirindi, my mother, my Inaa, my Mekiviewo. When our eyes met I saw many stars in hers. But I also saw tears and sadness, om addition to joy and may be hopelessness or may be like she was saying I’m done or maybe she was saying I told you at the waterside you will go to college, or like she was saying we did it for Christian Stephen. Or maybe she said none of these people here gave me food when I was hungry, gave me water when I was thirsty. I wept.

That moment, I realized that if my mother is to live another day, if my mother would ever smile again, if my mother will be happy again, it will depend on the decisions I make. I decided from that moment in 1992, that my mother will be my child and I will take her to the riverside and reassure her that she will be happy again. She will be the giver again. She will live as long as she would want to live. I took my mother back to Lagos with me. When I was posted to Ibadan, Odede (my sister’s daughter that came to live with me at age ten) and my mother accompanied me. From Ibadan I moved back to Lagos, and from Lagos to Port-Harcourt; my mother lived with me till I married my wife, Mimi.

Mimi and my children – her grandchildren, accepted and loved the women I loved most – Abirindi and Cecelia. One day, my mother told me “son, you know I worked hard, but I own nothing, and am so very happy I chose to be your mother instead of properties.” That night I thought about my conversation with mother, then I told myself I will work very hard so that I can get my mother those basic things she missed by paying my fees and providing for me when I was a child. I bought a house in Port-Harcourt, built a house for her in Yenagoa and provided for her to the beset of my humble abilities. My mother was never excited about material things. In fact, to my surprise, when I told her that I have built two small houses for teachers and finished the building of a Primary school in Yenebebeli, she stood up and hugged me. I saw my mother again the way she looked at me when I told her I “passed” and that I was going to grammar school.

Last year, upon roofing of the Yenebebeli Anglican Church, I came to Yenagoa, and in her bedroom, I whispered to her that I have just completed the roofing of the Yenebebeli church. Again, I got my reward on earth with the most beautiful smile I have seen in all my life. My mother told me on several different occasions, that she was living her dream vicariously through me. She once said that I was getting to do all the things that she would have wanted to have done. I knew then, as I do now, that God actually lived in my mother. As I write this, I am 100% certain my mother is with God. I asked for proof and God gave it to me.

God showed me the proof by the way she died. For more than eight months as the President of the International Society of Comparative Education, Science Technology, Nigeria, I had been preparing to host the world to a conference starting from the 3rd to 8th October, 2015. The conference date was shifted to 10th December through 14th December, 2015 to allow the Bayelsa governorship election to come and go. Now, my mother also knew that her son, a visiting professor to several institutions overseas, may not be around when she dies. She, like Chief G. M. Odumgba, had raised this issue with me. My mother also knew that by the tradition of the Epie/Atissa people when an elder dies, one must be present for four days and on the fourth day celebrate Ede Peletiemo, that day is set aside for relatives to celebrate the dead or better, put relatives to present themselves for recognition. For our custom and culture and tradition, it is a taboo not to be present. My mother was thinking of all these cultural and traditional commitments and wondering how I will be able to manage it. But, for the hundredth time, my mother did it again, proving to me the love, the affection and appreciating all that I have done for her (I know that whatever I did for my mother she had paid in full, I was only trying to thank her for the twenty-hours hours a day she gave in for me). That 10th of December morning, at about 5a.m. she came to my Hotel room at Aridolf Hotel and told me “mebidam” (I am leaving). Thinking she was going to the farm, I asked which of the farms – and she said “to Heaven”. My mother died 6:30am that same morning.

By dying on the 10th of December, the same day we were starting the conference, it allowed me to give my mother the respect and dignity she so deserved, allowing me to honour the four-day tradition of celebration.

I will always remember my mother. My sweet mother. Keep praying for me and my family. Do what you know best. Do not forget Ikolo, Famgbe, Swali, Yenagoa, Ogbogoro, Yes and Akaba and Ovom and Onopa and Agudama. I have named the street where you lived after you – Madam Abirindi Stephen Azaiki Street. It will probably be here for a long time. But, it is not in the naming of street that we will remember you. You will be remembered for your generosity, for your neighborliness, for your kindness, for your compassion and for your humility.

Albert Pike was right when he said “What we have done for ourselves alone dies with us; what we have done for others and the world remains and is immortal’’. You will never die. From your rotting body flowers shall grow and you are in them and that is eternity.

Prof. Steve Azaiki, OON

President, International Society of Comparative Education, Science and Technology, Nigeria.