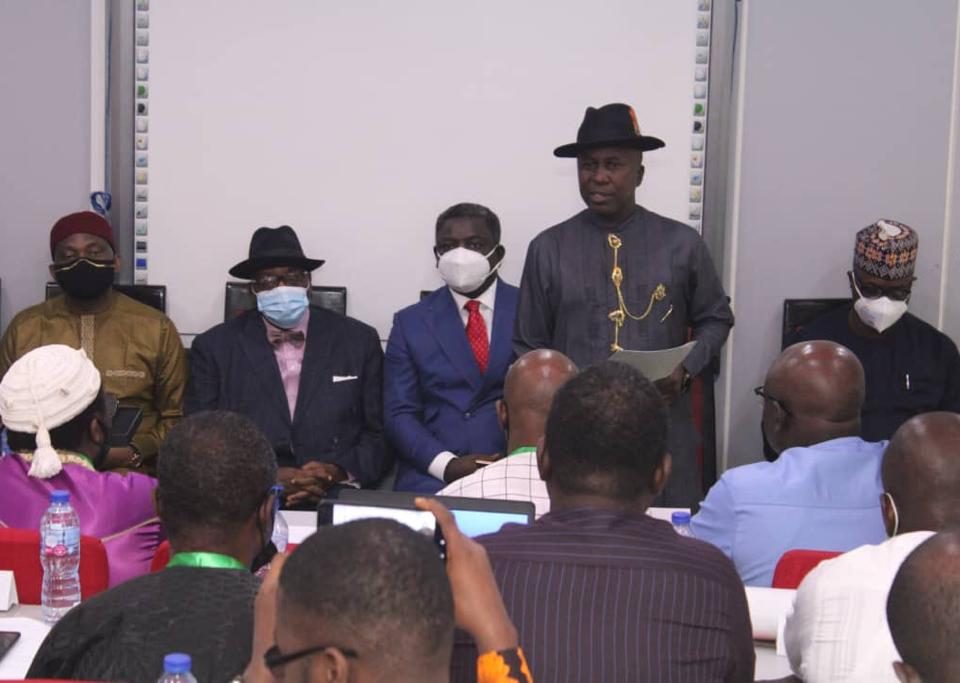

Respect your President, Azaiki tells Nigerians

May 11, 2014

FG SHOULD TAKE RESPONSIBILITY FOR N’DELTA DEV

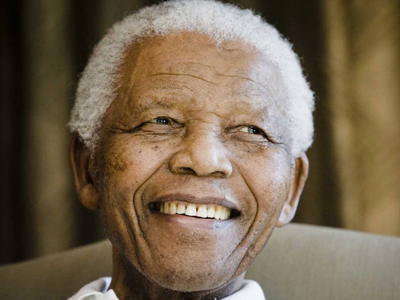

May 11, 2014When, a few weeks to his 95th birthday, former South African President Nelson Mandela’s latest health crisis notched a new high, I am sure I was not alone in nursing the private thought that, perhaps, he was being kept alive by all means medical science could permit, to at least prolong his life until his 95th anniversary, just five years shy of a Centurion. The world rose in celebration to mark that birthday on July 18, while Mandela remained in a Pretoria hospital, with varying reports of his beleaguered recovery, although your guess is as good as mine that Mandela, the global icon, is not in a race to become the world’s oldest living man.

Ten years ago, in an impassioned tribute to his fallen comrade and soulmate, the late Walter Sisulu (May 18, 1912 – May 5, 2003), Mandela wrote: “His passing was not unexpected. We had long passed the age when either of us would protest against the brevity of life.” As far back as 1964, when the Rivonia trial ended, both Mandela and Sisulu had reconciled themselves to the inevitable. “When we faced the prospect of the death sentence, we knew, we resolved to walk the plank, not protesting our innocence, but proclaiming the justness of our ideals and the certainty of their triumph,” Mandela stated in the tribute. Both men lived to see the triumph of their ideals, with the eventual deconstruction of apartheid in 1994, whereupon Mandela became the country’s first black President after non-racial elections.

I know that there is a strong sentiment, a feeling almost spiritual in a sense, in seeing a wizened, old patriarch or matriarch around. Even though drained of energy and mental alertness, the physical presence of such a person is a heartwarming rallying figure to whom the young and the strong direct their gaze and fond wishes. In a family circle, the presence of the patriarch or matriarch becomes a source of excursion, with clan members journeying from different abodes, just to spend some time, no matter how brief, with the venerated figure. Merely touching, or being touched by such a person has its own subliminal qualities, somewhat like tapping the blessings and drawing from the spiritual energy of the revered. Death changes all that, realigning the interaction to, at best, pilgrimage to the graveside, and supplication to the soul of the departed.

Incidentally, my first one-on-one encounter with Nelson Mandela was at a funeral in February 2007, when Mrs. Adelaide Tambo, wife of former ANC leader, Oliver Tambo, was being laid to rest. I stood in awe of Madiba, as the then South African President, Thabo Mbeki introduced me to him, describing me as one of Africa’s intellectuals. In the brief conversation with him, Mandela left me with a memorable and encouraging quote: “Africa will rise again.”

Mandela has lived life to the fullest. His has been a complete trajectory –and more. Few attain the status of icons; fewer still become legends, and not many can lay claim to being global legends. Nelson Mandela is all of those rolled into one. Considering the current state of his health, and except by some far-fetched miracle, he suddenly were to regain his vigour, there is nothing that Mandela could, and should, have done that he is in position to do now –whether about his family, or the ruling African National Congress (ANC). In any event, his well-publicised condition at the moment will put a lie to anything, or act, attributed to him at this stage. Yet, his ideals, principles, personal example, and legacy will endure, providing a compass for present and future generations.

I am wondering, however, just how much more Mandela can endure, before he is let go. Neither being hospitalised nor imprisoned is fun. Both imply confinement. I do not know Mandela’s tolerance level of invasive medical treatment; but to keep him going the way he has been kept alive requires the introduction into his system of all kinds of needles, liquids, nuclear rays (perhaps), and the relevant gamut of treatment needed. Still, he is confined to the intensive care unit, under constant monitoring. For 27 years, he was in prison, and most of the period he spent on Robben Island, breaking rocks, denied of the warmth of his family and of the opportunity of raising his children.

Africa could not have wished for a prouder son than Mandela. To the extent that history will always be a relevant subject in the future, the history of the world will not be complete without a discourse of Nelson Mandela. He was the rallying point for the emancipation of South Africa from the settler-colonialists, who sought to enslave the indigenous peoples in the land of their birth. But despite the tribulations that he, his family, and comrades and families suffered, Mandela emerged from prison in 1990, and became the quintessential definition of forgiveness.

Mandela performed an astonishing ablution for his torturers. A number of those who supervised his torment have long since gone: Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd was stabbed to death in the segregated Parliament in 1966; Prime Minister B.J. Vorster, who as Minister of Justice supervised the Rivonia trials, died in September 1983, at age 67; and President P.W. Botha died in October 2006 at a place called Wilderness in the Cape area, where he hibernated after he was ousted in 1989 by F. W. De Klerk, who eventually drew the curtains on the apartheid era.

But scarcely any of Mandela’s contemporaries in the epic and worthy struggle to overthrow the obnoxious apartheid system are around today. Oliver Thambo, Govan Mbeki (father of former President Thabo Mbeki), Walter Sisulu, and a host of others, some of them fellow Robben Islanders, are resting in peace. Every person, though, has an appointed time with the end. In the tribute to Sisulu in 2003, Nelson Mandela declared: “In a sense, I feel cheated by Walter. If there be another life beyond this physical world, I would have loved to be there first so that I would welcome him. Life has determined otherwise. I now know that when my time comes, Walter will be there to meet me”.

Ariel Sharon, Israel’s 11th Prime Minister, suffered a second stroke, and has been in a permanent vegetative state since January 2006. Early this year, there was a report that a high-resolution scan of his brain indicated some “activity,” but after that, there has been no positive development, and he remains on life support. Those who are in a position to take the decision must consider whether former President Mandela should be put through the same life support experience, which, in my opinion, is unnecessary.

At his age, and considering his staggering accomplishments, the world is prepared for the inevitable about Madiba. In Nigeria, advertisements for such an aged person would be headlined, “Celebration of Life”. The hordes, who have kept vigil outside the Pretoria hospital, where Mandela is on admission, and the millions around the globe who have offered prayers, know that, someday, Madiba will be no more. While this must not be construed as an advocacy of euthanasia, there comes a time when the guardians will have to decide on the next steps.

The hangman could have been deployed by the apartheid authorities almost 50 years ago; he could have been a target for assassination by those who did not want to see to the end of apartheid; or it could have been by other violent means. Chris Hani, Chief of Staff of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the ANC, was assassinated outside Johannesburg in 1993. His creator willed otherwise, and Nelson Mandela reached 95 years on July 18. I think he should be allowed to go peacefully, succumbing to natural causes.